To answer that question, we first need to find our bearings in the whole history of Egypt which covered over 3,000 years, to discover when, in its long history, the Hebrews were present in Egypt.

Egyptian history is divided by historians, for ease of understanding, into the Old, Middle, New and Late periods. Periods of invasion or unrest divide the Old from the Middle and the Middle from the New Kingdoms. The Late period is too late to be relevant to this study

Of the Old Kingdom, due to its great antiquity, we are limited in what we know. Very roughly it covered the years 3,000 – 2,000 BCE. During this time frame, the ‘Two Lands’ of ‘Lower Egypt’, the Delta, (the lower reaches of the Nile) and ‘Upper Egypt’, everything south of the delta, (the upper reaches of the Nile), were joined under one King forming Egypt as we understand it today. And it is thought, as there is no better explanation, that it was during this period, that the three Pyramids of Giza, and the Sphinx were built. The theory rests on very little evidence. A 3” statue of pharaoh Khufu, found in the Great Pyramid is given as evidence that he built this pyramid. Records show that Khafre, the next Pharaoh, repaired the second largest pyramid, which is seen as evidence that he built it also. And it is assumed that Menkaure, his son built the third. It seems to many, that the technical skills required to achieve these feats was not available at that time and would even be beyond the skills of the present day. So who knows? Perhaps they owe their origin to some more ancient civilisation that was destroyed.

The Old Kingdom was brought to an end by a period of instability and civil unrest, known as the First Intermediate Period. A king named Mentuhotep ll then seized power establishing his dynasty as the first of the Middle Kingdom, (approx. 2,000 – 1650 BCE.) During this period Egypt forged her iron grip on Nubia and Kush to the south, (today Sudan and Ethiopia), building a series of huge fortresses south along the Nile to maintain control of the rich natural resources of these nations. This became the primary source of Egypt’s wealth, and due to the stability and affluence it brought, Egypt now entered a period of intellectual flowering known to us as the Middle Kingdom. We have papyri from this period showing how advanced they were in mathematics, for instance. In this period, Egypt’s fame as a centre of learning became legendary, especially the city of Heliopolis. The physical city was a wonder of the world, known as the ‘City of Spires’ because of all the obelisks there, standing in and around its many Temples. Foremost among these temples was the huge Temple of Ra, now long gone. We see something of its magnificence at Baalbek in Lebanon, where a sort of daughter temple was built to Ra along the same lines. Massive stones. A huge edifice. The building itself predated this time in history, but as a centre of learning, Heliopolis now grew to have no rival. The temple of Ra was famous for its vast library, the accumulated knowledge of generations of priests for a millennium. Its fame was such that in later years, Greek scholars such as Thales, Homer, Plato, Pythagoras, Socrates and Hippocrates went there to study under the priests of Ra at his temple. Plato for 13 years. And it was during the Middle Kingdom that Abraham visited Egypt, because of famine in Canaan, around the year 1850 BCE.

But the city of Heliopolis, with its huge temple to Ra, a seat of learning and the collection of manuscripts in its vast library, is long gone. Alexander the Great, when he built the city of Alexandria, set up his own library which he filled with scrolls taken from many places, including the ancient contents of the temple of Ra at Heliopolis. Its huge stones were also taken and having lost its treasures and its purpose, the city slowly died. What remains is under the sprawling suburbs of Cairo. Only one obelisk is still standing to mark the spot of Ra’s temple, in a north-eastern suburb of Cairo.

The Middle Kingdom was brought to an end by invasion. People from what is now Syria took control of the country. The Egyptians called them ‘Hyksos’, meaning shepherd kings, and despised their memory ever after, managing to expel them after about 100 years. But it was under the Hyksos rule that the Hebrew Joseph was sold by his brothers as a slave, ending up in Egypt where he rose to be the right-hand man of the Hyksos king. When famine struck the region, Joseph arranged for his family to settle in Egypt’s fertile delta, where they could sit out the famine. This they did very comfortably, and in this pampered position, grew in numbers very rapidly over the course of the next 100 years, so that when the native Egyptians finally got rid of their Hyksos invaders, they discovered another invasion had taken place. Others, the Hebrews, related to the hated Hyksos invaders, had made themselves comfortable in Egypt, and grown in numbers to such an extent that the Egyptians feared them. The opening text of the book of Exodus gives confirmation that this is the correct time period for the Hebrews entering Egypt. The expulsion of the Hyksos was more than a dynasty change. This was a change from invaders to native Egyptians regaining control. So when the text of ‘Exodus’ says the ‘A pharaoh arose who did not know Joseph’, it is entirely correct. Joseph had been a friend of the Hyksos, who were the hated enemies of Egypt. This era when the native Egyptians regained control is known to us as the ‘New Kingdom’.

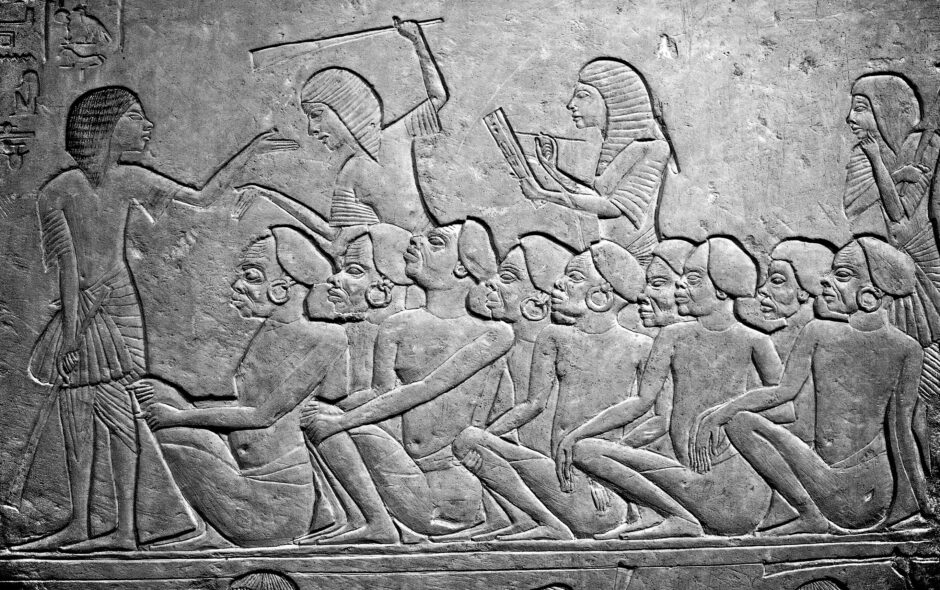

The first and second kings of this ‘New Kingdom’, Ahmose and Amenhotep l, re-established Egyptian control, and probably, during the time of Amenhotep l, the Hebrews were forced into slavery. But still they grew in numbers, until under the next pharaoh, Tutmose l, they seemed such a threat to Egyptian security that the pharaoh ordered their baby boys to be drowned in the Nile. This brings us to the story of the rescue of the infant Moses by Tutmose’s own daughter, Hatshepsut. She was probably only a child herself when she found him. And true to the nature of most little girls, could not leave a helpless infant to die. She was determined to keep him. Probably living away from her parents, growing up in the harem, she was able to keep this fact from her father.

And now we can start to answer the question at the heading of this article. Hatshepsut, as we know, made herself pharaoh for 22 years, and it is not until after her death, during the reign of Tutmose lll that we see the great benefit that Egypt derived from these slaves. Tutmose lll was determined to ring fence Egypt against the threat of invasion occurring again. He decided to take the war to the enemy and defeat them on their own soil. But this was an enormous undertaking. Canaan and Syria consisted of many city states joined in strong alliances. Their lands were fertile, with well-established trade routes, making them very wealthy. War would require Egypt to commit massive resources for a long period of time, to achieve success. She was wealthy, she had the resources of Nubia and Kush, but her enemies in the north were also powerful and wealthy.

However, the Hebrew slaves became Egypt’s secret weapon. Tutmose could remove tens of thousands of Egypt’s peasant farmers and train them as his crack troops because the huge population of slaves could do the work of these farmers. In the delta, they could grow all the food needed by the country, year after year, and store it in the store cities they built for this purpose, the cities of Ramesses and Pithon. This continued year on year, without impoverishing Egypt. In fact, Tutmose lll went to war, almost every year for 20 years. In that time, he forced the city states of Canaan to submit to Egyptian rule and had the manpower to garrison them and keep them under control. Egypt could now bleed the wealth of Canaan as well as Nubia and Kush. And after gaining control of Canaan, Tutmose set his sights on Syria. With such a good supply of troops he had the manpower to overwhelm Syria also, taking Egypt to its greatest heights of Empire. An Empire she could never have built without the slaves as an essential part of her war machine.

The wealth Egypt accrued due to these wars was poured into the temples we see standing now. So when we visit Luxor today and see its great monuments, we are looking at temples built from the wealth taken from Canaan and ancient Syria, largely by Tutmose lll during the early New Kingdom.

Tutmose lll attributed his great military success to the help of his god, Amun, whose main temple was in ancient Thebes, at Karnak. Here he added to the size and splendour of the temple in honour of Amun and supplied the temple with huge revenues, from the booty he had taken in his wars, so it could employ 1,000 priests in the service of his god. And this wealth spilled over into subsequent reigns when further building was done such as during the reign of Tutmose’s great grandson, Amenhotep lll who built the temple of Luxor.

Looking objectively at the facts, one could say that Egypt would never have been able to build the great northern empire she did, extending as far as the Euphrates River, without her Hebrew slaves. She would never have gained the wealth she did, which enabled her to build the magnificent structures we see today, without the Hebrew slaves supporting Tutmose’s war machine. And when the slaves left, in the next reign, under Tutmose lll’s son, Amenhotep ll, Egypt entered a slow decline. She had to recall her soldiers from the north and return them to growing crops or the country would starve. She was forced to make peace treaties with her sworn enemies in Syria, or risk invasion again. But by losing control of Syria, she lost not only territory but revenues. And when the Hebrews entered Canaan forty years later, it signalled the end of Egypt’s revenues from Canaan also. It took some years before the unsophisticated Hebrew pastoralists could take the walled cities of Canaan, so they continued living in tents in the countryside as they had before entering Canaan. So for a time Egypt kept control of many cities, especially those on the coast. We see something of this in the relevant Armana letters. But in time, as the Hebrews organised themselves under their Judges and early kings, Egypt lost Canaan also. So in conclusion, it could be said, that the Hebrew slaves helped Egypt reach her highest point of Empire, gaining control of the Levant as far as the Euphrates river. Then with their departure, the Hebrews brought about the beginning of the end to Egypt’s northern empire.

The story from the birth of Moses to the crossing of the Red Sea is covered in the two following books:

- ‘The King and her children, the story of Hatshe

- ‘The Napoleon of Egypt, the story of Tutmose lll.’